Intelligence to Risk

Every good story includes a capable, if not impressive, antagonist. We’ve even become accustomed to celebrating adversaries and anti-heroes. The business world has plenty of antagonists – workplace, and workforce equilibrium changes, pandemics, supply chain disruptions, de-globalization, central bank actions, foreign currency exchange rates, inflation, recessions, cyber threats, conflicts, wars, persistent uncertainty, and the list goes on.

Of course, it’s helpful to understand which antagonists are threats and which are risks. Threats become risks when reasonable controls are absent or lacking. In business, the distinction between threats and risks may be clear, but in my experience, there is nuance in both the analysis and the final classification.

Business - our protagonist - needs an information advantage. I mean an ongoing and durable advantage, like saving $15K on vehicle MSRP or shaving 20 minutes off the daily commute home. Let’s call this information advantage – intelligence.

Business needs intelligence to identify threats and classify risks. Some risks deserve a swift response, or the probability of loss increases, and loss (life, revenue, etc.) is always regrettable.

Intelligence implications, as they pertain to business risk, are rarely straightforward or intuitive. Let’s call this antagonist, complexity, which leads to the shadow of executive irrelevance. It’s a Mount Everest-sized adversary.

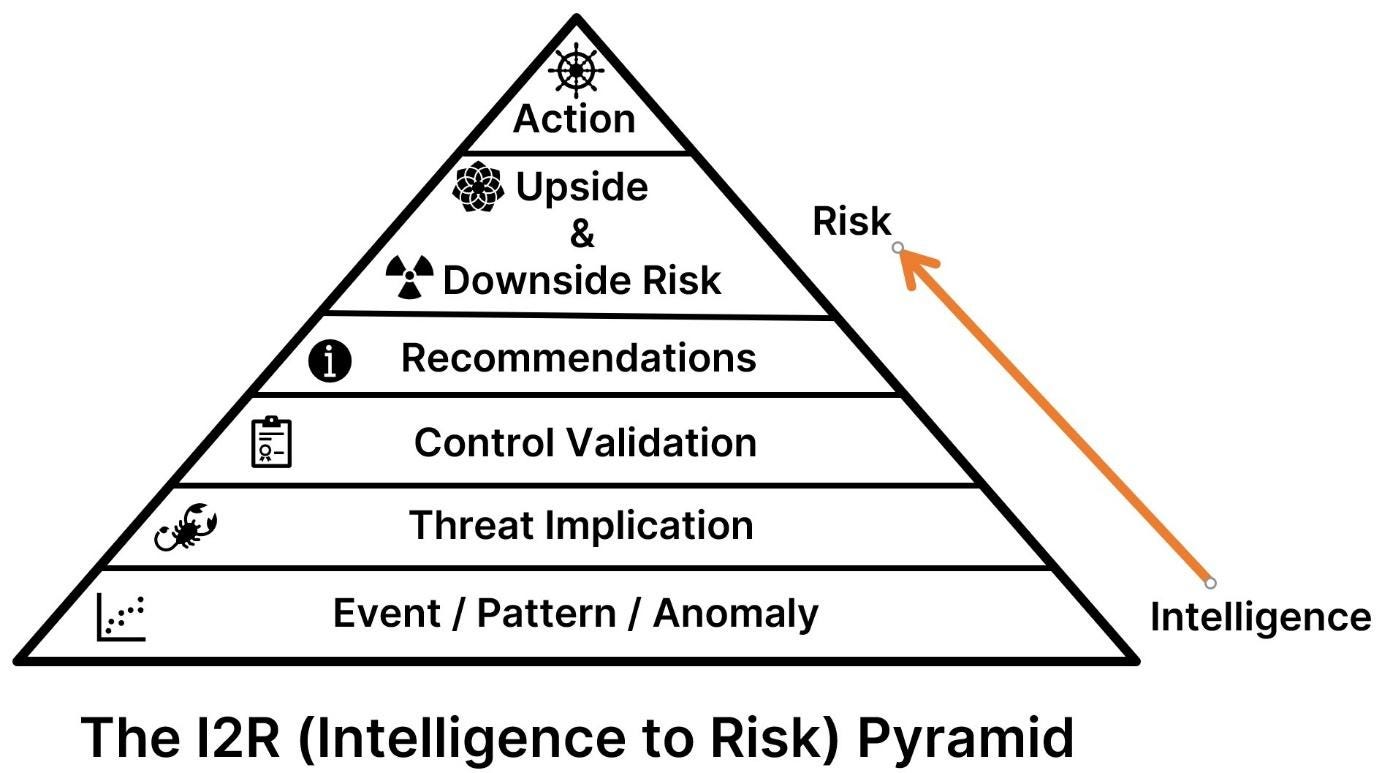

To simplify the path from intelligence to risk (I2R), in the summer of 2022, my Recorded Future colleagues (Dylan Davis, David Carver, and Harry Matias) and I sat down with a whiteboard to formalize our process. The below pyramid is how we think about identifying and managing risks.

A few caveats here. First, the pyramid is meant primarily for the private sector. The public sector (e.g., law enforcement, military, and intelligence agencies) uses intelligence to accomplish kinetic outcomes – a formal designation for kill, capture, and prosecute-type actions.

Second, this workflow is for strategic reporting rather than operational outcomes. In this context, “strategic” refers to work that requires a human brain (even beyond the present bounds of AI). “Operational” is my designation for automation work accomplished with a machine.

Third, we chose a pyramid because as we move up the stack, each successive layer is a smaller domain with a corresponding increase in performance difficulty to ultimately achieve “action.” Dylan points out it’s a fancy way of saying that if you write threat reports for a living (in the private sector), think about using this pyramid to structure your workflow and deliverables for maximum impact and value.

All intelligence may deconstruct into an event or a series of events (which creates patterns and anomalies within patterns). Broad visibility across different types of events is necessary to enable risk evaluation. In the coming months, I plan to write more on this topic. It’s what Recorded Future’s President – Stu Solomon – calls Foundational Intelligence.

The “Threat Implication” layer is where analysts earn their paychecks. Second-order thinking - identifying non-obvious and perhaps non-intuitive implications - is the differentiating skill between good and great. It may be mentally taxing, but the results are valuable. A broad background in geopolitics and cyber, as well as knowledge of current events, is a prerequisite for identifying threat implications. This step is where an answer takes shape for the two fundamental executive questions: “So what?” “Now what?”

Control validation answers a reoccurring question: “do our controls work as intended?” When the threats become technical (i.e., new malicious code – “malware”), we know from experience that the answer is often “no.” This stage moves a threat from general thesis applicability to the exposure of a potential control gap or the reaffirmation that controls are functioning well. To properly understand internal controls, multiple individuals from across an organization are often required to provide input.

The “Recommendations” step is necessary for leadership to consider options, each presenting different risks. Ideally, this step produces one strong short-term and long-term recommendation coupled with a business justification that includes resource trade-offs.

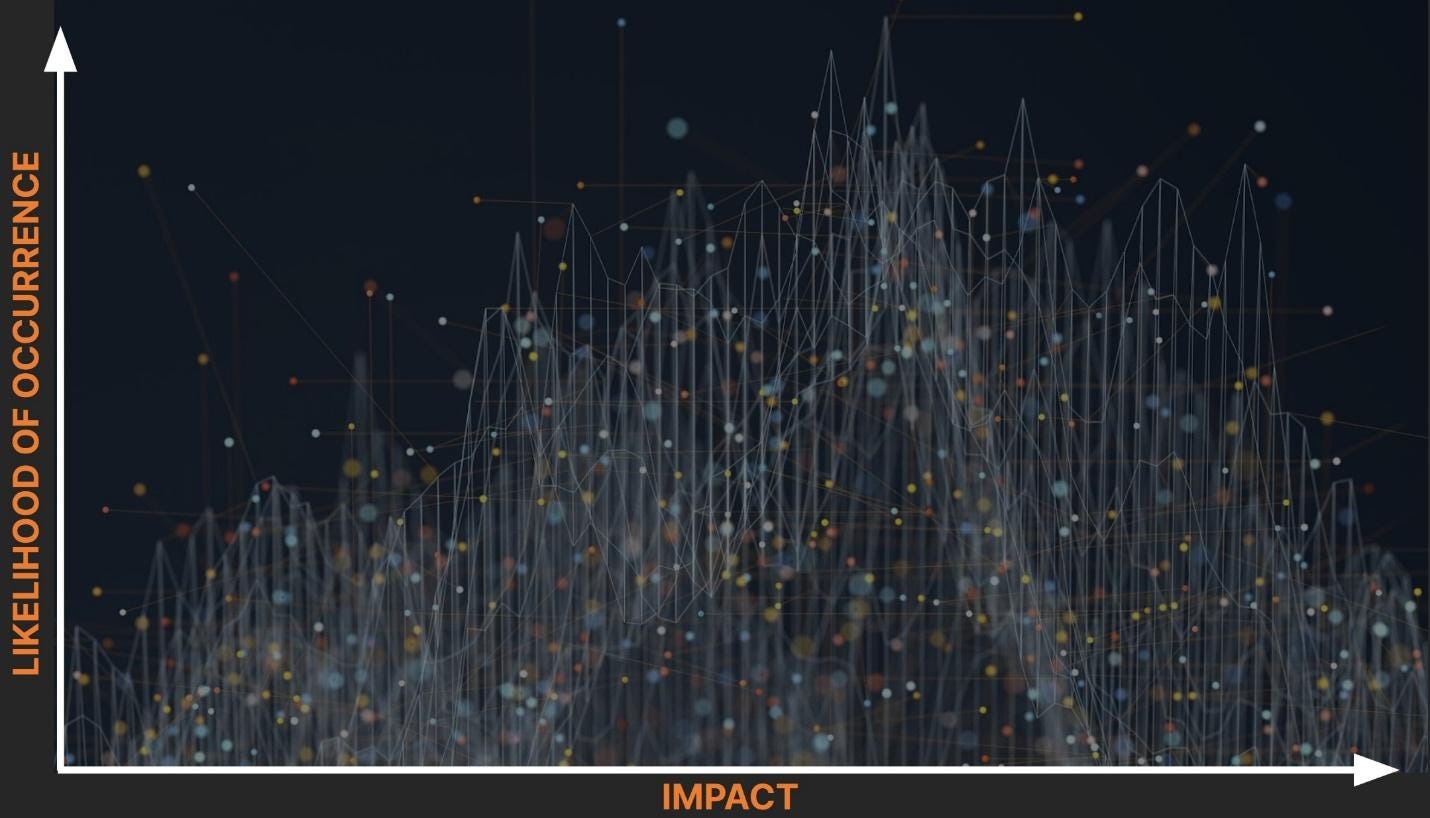

“Upside and Downside Risk” involves articulating residual risk from the preceding recommendations. Most enterprises prefer to qualify risk using the likelihood of occurrence and impact paradigm. Once the downside risk is measured (however imprecisely; I will always advocate for quantifying risk), upside risk may act as a counterbalance. I’ll save the five downside risk categories for another day; however, considerations for upside risk include speed, market share, customer churn reduction, increased engagement, and innovation.

Finally, the “Action” pinnacle is when a business leader or leadership team decides to act, or not act (which is also a valid outcome) based on an articulation of the I2R steps and an understanding of current business focus and constraints.

I2R beta testers previously suggested a “feedback” step was warranted, but in our experience, it’s uncommon for executives to provide feedback consistently.

Our desire is for this framework to help security practitioners and executives alike. In the coming months, I’ll work on adding specific examples to this thread. Connecting intelligence to risk and executive relevance is a challenging process. We think this is a practical tool to help the world’s intelligence professionals and business leaders.

It’s time to support the protagonists.